“The wars of the next century will be about water.”

-Ismail Serageldin, Vice-President of the World Bank

Introduction

This study focuses on one of the newer phenomena involving water management: the privatization of water. I have chosen a couple of countries’ responses to water management and privatization as my primary comparative framework for this discussion. England, Wales, South Africa, and Bolivia fit onto a continuum of differing governmental systems and agendas, Human Development Index rankings, GDP, GNI, literacy ratings, infant mortality and much more. The effects of water privatization on certain lower income communities in these countries are unique, yet almost always devastating.

This issue is complex, but there are key points to recognize. In almost all cases, water privatization has turned out badly for the people. The water companies seemed to have worked independently from the governments and the people they are supposed to serve. Hence there was not a publicized, pre-met contract that the people who would be affected could agree and modify if needed. The governments studied in this paper (commonly) never ask the people if this is what they want – the investment of outside water management companies to handle their water issues. Nor do they explain the likely drastic increase that the water companies will impose on the peoples’ water and sewage bills to whatever degree they feel necessary, or if there will actually be an improvement in their water services. The studies indicate that where ever water privatization occurs it will always need the partnership of the people affected, local and national governments, and the water companies.

Section I describes the current crisis in world water management. Section II analyzes the current world situation regarding water privatization. Section III examines the histories of privatization and current situations in England and Wales, South Africa, and Bolivia. Part IV includes some of the non-governmental organizations in these three countries that are working on the water privatization issue. Part V details some recommendations on how to make privatization work.

This issue is complex, but there are key points to recognize. In almost all cases, water privatization has turned out badly for the people. The water companies seemed to have worked independently from the governments and the people they are supposed to serve. Hence there was not a publicized, pre-met contract that the people who would be affected could agree and modify if needed. The governments studied in this paper (commonly) never ask the people if this is what they want – the investment of outside water management companies to handle their water issues. Nor do they explain the likely drastic increase that the water companies will impose on the peoples’ water and sewage bills to whatever degree they feel necessary, or if there will actually be an improvement in their water services. The studies indicate that where ever water privatization occurs it will always need the partnership of the people affected, local and national governments, and the water companies.

Section I describes the current crisis in world water management. Section II analyzes the current world situation regarding water privatization. Section III examines the histories of privatization and current situations in England and Wales, South Africa, and Bolivia. Part IV includes some of the non-governmental organizations in these three countries that are working on the water privatization issue. Part V details some recommendations on how to make privatization work.

I. The World Water Situation: Why Privatize?

There is currently a global water crisis because there is a finite source of freshwater on this planet. Available freshwater amounts to less than one half of one percent of all the water on the earth while the rest is sea water or is frozen in polar ice. Increased urbanization, deforestation, water diversion, industrial farming, pollution, and general development projects have strained our finite resource. Every twenty years our global consumption of water doubles, which is more than twice the rate of human population growth. By 2025 the demand for freshwater is expected to rise to 56% more than the amount that is currently available and 2/3 of the world’s population will experience water stress (“Water Industry”). We are irreversibly diminishing our world’s water capital (Barlow 1).

Twelve percent of the world's population uses 85 percent of its water, and these 12 percent do not live in the Third World. The UN states that currently more than one billion people lack access to fresh drinking water (Barlow 1). One in five people in the developing world do not have access to clean water. In the 1990s, the number of children killed by diarrhea, a result of unsafe and unsanitary water – was more than the number of people killed in World War II (Joy and Hardstaff 7).

Governments and transnational groups are taking action to try to alleviate some of this strain by promoting the privatization, commodification, and mass diversion of water (Barlow 2). Advocates for privatization say that corporations can invest more money and improve efficiency for water filtration and allocation, thus allowing the poor to get their share. However, a multinational corporation’s main goal is to satisfy its shareholders by increasing profit. Thus some case studies show that the privatized water is delivered to those who can better pay for it – whether that be a wealthy individual, city, or development area. These prices can be well beyond what the poor can afford. Hence the poor remain thirsty.

There are a couple of reasons a government may wish to privatize public essential goods such as water. One belief is that the private sector could better meet water needs. A second idea is that more business and less government is better. A third motive is that private water companies could provide water services cheaper and more efficiently. Another reason is that a government may be indebted or need instant funding, so selling off public goods to the private sector is a quick cash option.

There are a couple of reasons a government may wish to privatize public essential goods such as water. One belief is that the private sector could better meet water needs. A second idea is that more business and less government is better. A third motive is that private water companies could provide water services cheaper and more efficiently. Another reason is that a government may be indebted or need instant funding, so selling off public goods to the private sector is a quick cash option.

The CATO Institute website explains that 97% of economically disadvantaged countries water services are under public sector control and often are mismanaged (Segerfeldt). This causes a billion people to not have access to clean water. Some poor governments have turned to business for assistance in resolving their water management issues, and, according to the CATO institute, they often provide good results. Their reasoning states that in impoverished countries, water privatization provides more people to access to clean water than those without such investments.

Moreover, there are many examples of local businesses improving water distribution. Superior competence, better incentives and better access to capital for investment have allowed private distributors to enhance both the quality of the water and the scope of its distribution. Millions of people who lacked water mains within reach are now getting clean and safe water delivered within a convenient distance (Segerfeldt).

With the conditions all over the world illustrating the harm of what water privatization has done to communities, the case studies have proven that the above statement is very flawed.

How Water Privatization Should Work

Water privatization is essentially when a private entity buys and sells water services. The private company is invests in some to all of the water service components of a particular region. These components include the filtration, purification, and infrastructure involved in efficient, clean, and fairly allocated water management.

There are two types of water privatization, the "French Model" and the "British Model." The French Model is a public-private partnership where the state continues to own the assets and is involved in the monitoring and decision making of the service delivery, but the actual operations and planning of water services are undertaken by a private entity. The British model is where the entire water systems, the water collection, reticulation, and sewage treatment are sold to private firms. The monitoring and regulatory oversight in this model of privatization remains the responsibility of the state (McDonald and Ruiters 23).

Although few good models exist in reality, there are a couple of criteria that should be met for effective water management. First, the basic ecosystem and human needs for water must be met. There should be a guaranteed basic water quantity required under any privatization agreement for all living things. Basic water requirements for users should be provided at subsidized rates when necessary, especially for reasons of poverty.

Transparency of and consensus of the people, local government, and water company on water service policy is essential. This partnership creates a more informed public so that they are aware and agree on certain stipulations. Water privatization contracts should always be public, transparent, include appropriate language for all readers, and include all affected stakeholders.

The contracted responsibilities of the water companies should include pre-arranged profit caps so that the public is never charged above a certain amount. Companies must prove that there is a necessary investment change in water management infrastructure to attest water price hikes. An accurate cost-benefit analysis should always be performed before costs ever rise. They should provide the public information on the need for increased rate hikes and the links to improvements in service. A provider should be allowed some freedom in water management decisions, but not be able to renegotiate the agreement when profits decline.

The partnership and transparency between governments and the water companies is critical. Governments should define and enforce water-quality laws. Governments should continually monitor water quality to provide oversight of the private companies. They should acquire independent technical assistance and a continual contract review should be standard. Governments should allow for multiple bidder consideration, preferably from local companies so absentee ownership is less of an issue, thus encouraging competition and no monopoly of a community water supply.

II. Current World Water Privatization Situation

With the current water crisis, water is one of the investment opportunities of the 21st century. It is already a $400 billion a year industry, 30% larger than the pharmaceutical industry (“Water Industry”). Around 9% of the world’s water supply is privatized. The three companies that dominate the water privatization industry are the French companies Vivendi and Suez, and the German company RWE (Barlow 2).

An evaluation regarding if privatization is truly needed comes into question depending on the region. The amount of investment needed in certain areas’ water systems can alter the need for the privatization. In the United States for instance, from 1880-1920, different cities had differing water filtration and purification system needs. Cities that were located on oceans often drew their water from mountain springs, and therefore required little in the way of filters because of the purity of their water sources. Cities that drew their water from major rivers confronted large public health problems because of the upstream polluters, where the dumping of raw and untreated sewage was a common occurrence. Cities that drew their water from the rivers were therefore required much larger and more elaborate filtration and purification systems (Troesken 929). The investments needed for water filtration, purification, infrastructure, and allocation in certain areas range from a little to extremely large depending on the environmental, water scarcity, geographic, and demographic considerations.

The World Bank is one of the largest advocates for water privatization, fronting the money for companies to buy water utilities in developing countries. The transparency of water commodity negotiations is negligible once private, profiteering companies have a say (Barlow 29). The public do not have as much power when they do not know what is going on behind closed doors.

Due to special business laws and contracts, some companies do not even have to sufficiently explain to the public regarding violated contamination standards. People die in such cases, as happened in Walkerton, Ontario, when 7 people, including a baby, died from E. Coli contaminated water. The company’s testing laboratory that had subcontracted their water, gave the results of their tests to the public officials, of whom were not trained to understand the tests (Barlow 30).

When companies own your water you don’t have a choice but to comply with whatever monetary amount you are required to pay. A federation of public trade unions worker David Boys says:

Your clients are captive because they can't decide, 'Well, I'm not going to

buywater anymore, I'm not going to turn my tap on,'" he says. "You can't do

that.You can switch from Coke to Pepsi but you can't switch from water to...

what (Carty 1)?

Water scarcity can also create social, political, and economic impacts on a region when another region is providing the community’s water. When one company or nation provides another area’s water supply, that nation can hold power over another and threaten to cut off water supplies if their mandates are not maintained (Barlow 2). Citizens’ rights could also be degraded when corporations control their water rights and they can bypass individual and government interests. Corporations, who can work beyond transnational boundaries, can impose their interests on governments thus causing democracy to decay.

Medically and financially, the poor end up paying more for their water than do the rich because when they cannot afford it. They often have to obtain water from illegal sources or resort to dangerously polluted bodies of water. World Bank experts state that when the poor have to pay more than 5% of their income for water they will stop paying for it (Barlow 20).

Water is also a major economic development asset. A recent study found that investment in basic water infrastructure was the second most critical topic for emerging economies. By investing in their water systems, governments increase their country’s water quality. Increasing the supply of potable water then makes that area more attractive to international investment and development because water becomes available for industrial purposes. Because water systems are extremely capital intensive, the cost burden to a government can impact other sectors of fiscal allocation (Gleick et al. 35). Thus, why not involve the private sector in making the water management decisions?

The following information will illuminate some of the facts regarding the water privatization controversy. Despite being vigorously promoted in the policy arena and having been implemented in England, Wales, South Africa, and Bolivia, privatization has not achieved neither the scale nor benefits anticipated.

III. Case Studies

The following countries have differing histories regarding why water privatization occurred. The outcomes of all these case studies are essentially similar with the overarching trend being that those who are affected the hardest are the poor.

England and Wales

Basic Statistics: The United Kingdom includes Northern Ireland, England, Wales, and Scotland. Considered “high” on the Human Development index, this conglomerate of countries has a 99% literacy rate, 5 (per 1,000 births) infant mortality rate, and 78.54 is the average life expectancy. The UK also has one of highest average per capita gross domestic product incomes in the world of U.S. $36,851. This case study focuses on the water privatization history in England and Wales.

The following information will illuminate some of the facts regarding the water privatization controversy. Despite being vigorously promoted in the policy arena and having been implemented in England, Wales, South Africa, and Bolivia, privatization has not achieved neither the scale nor benefits anticipated.

III. Case Studies

The following countries have differing histories regarding why water privatization occurred. The outcomes of all these case studies are essentially similar with the overarching trend being that those who are affected the hardest are the poor.

England and Wales

Basic Statistics: The United Kingdom includes Northern Ireland, England, Wales, and Scotland. Considered “high” on the Human Development index, this conglomerate of countries has a 99% literacy rate, 5 (per 1,000 births) infant mortality rate, and 78.54 is the average life expectancy. The UK also has one of highest average per capita gross domestic product incomes in the world of U.S. $36,851. This case study focuses on the water privatization history in England and Wales.

Water Privatization History: Water services were taken over by local authorities in the late nineteenth century. Since then, a pattern of mixed ownership has been running certain water companies. Some large inter-municipal operators and some private water supply companies actually had a maximum profit cap of 5% (Lobina and Hall 1).

In 1974 the water service industry was reorganized. The 10 Regional Water Authorities (RWAs) were created. Each company covered a river basin area; each was responsible for water quality, water supply, and water sanitation throughout the area. The government appointed the authorities, so the government was not accountable to the local government any more. The Board meetings were open to the public, until they were made secret by the Thatcher government in 1983 (Lobina and Hall 1).

Twenty nine privately owned statutory water companies were also established. The statutory water companies supplied water to areas nestled within the regions of the water authorities. The RWAs provided water to the remainder of the population and were responsible for all the sewer services.

The effects of the reorganization: The efficiency gains were tremendous. The RWAs reduced the number of employees from 80,000 to 50,000 (Lobina and Hall).

The water industry in England and Wales was privatized in 1989. It is an example of the most complete water privatization ever recorded. There were several pressing situations that the Thatcher administration felt prompted to address using the privatization model. Supposedly England’s already strained water resources and underinvestment in the water industries was creating declining water quality throughout the 1970s and 1980s (Bakker 369). Situations of water scarcity and quality were also an issue. All but one of England’s 33 major rivers were (and still are) suffering, some with less than a third of their average depth (Barlow 14).

England used water privatization as a conservation incentive. By increasing prices, hopefully more people would use less water.

The neo-liberal Thatcher administration argued in favor of privatization claiming that: the private sector would be more efficient; private companies would better be able to finance the large investments needed (Barlow 14); privatization would introduce competition, a profit oriented objective for enterprise in place of vaguer 'public interest' criteria; and water privatization would remove political interference in the management of enterprises and capture by special interest groups (Saal and Parker 255)

The claims were not supported by evidence from comparative studies or international reviews of the actual performance of public and private sector water companies. The more basic motive was that the Thatcher government neo-liberal economic policies to push for the reduction in the role of the state and reducing public sector borrowing as low as possible. The RWAs were not able to raise funds for investment as well as before the Thatcher administration government policies, thus this was further justification for privatization.

Although the government originally proposed water privatization in 1984, there was a very strong public campaign against the proposals. The issue was thus abandoned until the 1987 election. The directive was won in 1987 and the privatization plan was rapidly resurrected and implemented.

At privatization, with the exception of the transfer of environmental regulation and river maintenance activities to the government agency, there was minimal restructuring of the industry. The RWAs became the water and sewer companies, while the water companies gained new freedom to raise capital and pay dividends (Saal and Parker 259).

What is the real track record like for the privatization firms of Great Britain? Public Services International reports that in England, between 1989 and 1995 there was a 106% increase in the rate charged to customers, where the profits of the water companies increased 692% (Barlow 26). Some of the salaries of the directors of these companies have increased over 700%, while the residents of the areas they service have populations where 50% have had their water disconnected because of price hikes.

In another study, low-income families were found to spend an average of about 4 percent of their weekly budget to pay for water, which was considerably higher than the national average of just over 1 percent. Another survey found that 75% of those on the UK’s Income Support had difficulty paying water bills and that water debt rose faster than any other section of debt for low-income families (Bakker, “Paying for Water” 149).

During 1994 alone, almost 2 million households in Britain defaulted on water bills, and by the end of that year more than 1 million (5%) were behind with their payments. Some bills have risen above the rate of inflation throughout the 1990s. The proportion of income of lower-income families spending on water and sewerage bills increased faster than that of higher income families (Bakker, “Paying for Water” 150).

Great Britain did take steps, however, to try and equalize the water bill rates according to family's supposed income levels. One very imperfect approach was to evaluate the value of a family's property and somehow parallel the water charge rates to how much their property value was.

Under the provisions of the Water Industry Act in 1999, disconnection of

domestic water consumers, and other non-private sector users (schools,

children's, residential care homes, hospitals) was prohibited as also the use of

limiting devices (e.g. trickle valves) in the case of non-payment. Households on

low incomes or from vulnerable groups have alternative charging options

available and consumers have the right to free optional metering. Only

"non-essential" uses such as the use of garden sprinklers of filling swimming

pools are subject to mandatory metering (Bakker, “Paying for Water” 153).

According to one study, the increase in water charges across the water industry service areas in England and Wales was due to increased capital expenditure in the industry. Two claims of improvement were the supposed increase in drinking water quality and lower environmental impact of water production. The reasons and validity for the rapid increase in water charges, however, have been debated.

England’s water companies are also considered some of the worst environmental offenders in the world. They have been successfully prosecuted over 128 times (Barlow 26).

Public authorities, however, still operate the municipal water industry in Scotland and Northern Ireland. Since England's and Wale's privatization, the Scottish parliament has discussed the water industry but privatization has been rejected except for some BOT-financed treatment plants.

England took steps to revise their water policy to make it work more democratically. This indicates that through federal policy change that water privatization can work more effectively although it will probably never be perfect. There are plenty of technical papers written about the water service industry in the United Kingdom. Unfortunately there are little to no resources discussing the citizens’ perspective on water privatization. Nor are there readily available studies discussing the specific environmental degradation effects caused by England’s water companies.

South Africa

Basic Statistics: South Africa is considered “medium” on the Human Development index. It has an 86.4% literacy rate, 61 (per 1,000 births) infant mortality rate, and 42.3 is the average life expectancy. South Africa has an average per capita gross domestic product income of U.S. $5,035.

Basic Statistics: South Africa is considered “medium” on the Human Development index. It has an 86.4% literacy rate, 61 (per 1,000 births) infant mortality rate, and 42.3 is the average life expectancy. South Africa has an average per capita gross domestic product income of U.S. $5,035.

Water Privatization History: After the South African apartheid ended in 1994, the new government organized a new water system. Before apartheid the minority white population, just 15% of the population of South Africa, consumed most of the country’s water. One-third of South Africans had no access to clean drinking water. The director-general of the Department of Water Affairs in South Africa states that they supplied over 7 million people with water by improving and building new infrastructure (Carty 1).

The World Bank, however, assisted in this transition from horrendous water accessibility to a “better situation.” The World Bank worked and is still working with municipalities and the national government to “advise” on public policy. However, the stipulations require that the South African governments comply with their stipulations or they will not be given financial assistance to use for bettering water projects. This was how privatization of water began in South Africa (Carty 1).

Some cities in South Africa allowed for the French and British water corporations to take over their water utilities. In other places, where some of the utilities remained public, they were forced to reduce subsidies and operate like a private business. Henceforth, the “Water for Profit” slogan became a common slogan for the South African people.

Differing communities in South Africa, however, have been affected by water privatization differently. In an area called Ngwelezane, 80% of the 20-30,000 working class, some scraping by in agriculturally based jobs, had to pay for their water to come from standpipes. This is a very poor community, with a high percentage of them suffering from AIDS and other diseases.

In 1997, the municipality began charging the people for their water to advance their stated goals of “stop people from wasting the water (Carty 1).” Prepaid water meters were installed in the community. Using a money card, those who could afford it, only bought the amount of water they needed. The water meter device would often, however, break down and peoples’ money would still be taken while receiving no water. Nonetheless prepaid water meters are continually being installed all over the country (Ka-Manzi).

The relationship between how much water a person needs and how much they could afford created a loss in social capital for the region. The restriction of allowing to only get the amount of water they can afford exacerbates further suffering of those who are sick and poor. The poor are already very careful about their water consumption. The people who had taps in their own homes had their water turned off and were told “No money – no water (Carty 1).” In 2001 alone, approximately 500,000 South Africans were cut off for non-payment (Taylor).

In some South African townships, there are armed security guards, “water enforcers” who come in and cut off the water supplies to civilians who are lucky enough to have indoor plumbing. Single mothers, the unemployed, and poor citizens would then have to succumb to the charity of their neighbors and allow their life to revolve around fetching pots of water to and from their residence to subsist. The water for cooking, cleaning, washing, bathing, and flushing of toilets is continually fetched all day. Before their water was cut off, some citizens reported a monthly water bill increase of 300 percent (Carty 1). Residents in the township of Kanyamazane watched their average water bill rise from 7 to 300 rand a month – a 4,185% rise.

People are angry. Riots and mobs are frequent. Some people, like grandmothers and other wholesome citizens are finding ways to illegally reconnect their water sources in the middle of the night. Ignoring the risks of arrests and beatings, some activists find ways to reconnect water for communities refusing to pay prepaid water installations. A man dubbed the ‘God of water’ has been reconnecting water and electricity for the past seven years. A new black market has formed for water.

Since the 1992 Sustainable World Summit in Johannesburg, the work of 20,000 demonstrators has been given attention. Since many of the protests, the South African government has changed its water policy. Calling it the Free Basic Water policy they promise to provide a minimum amount of water for free on a daily basis (McDonald and Ruiters 99). Is 6 kiloliters per person, or 6,000 liters per household per month, an adequate amount? Depending on the area “many say they have yet to see their minimum daily amount of free water (Carty 1 and Taylor).” In areas like Tshwane, although “free water” is available to everyone no matter what the income level, the first water six kiloliters are charged and then rebated on later bills so to make the user acknowledge the actual production cost (McDonald and Ruiters 99).

Those who could no longer afford it resorted to getting their water from the bacteria infested lakes and rivers. The worst cholera outbreak in recent South African history was recorded thereof, where around 350,000 people were infected with cholera, and a little below 300 people died (Carty 1 and Barlow 33).

The water companies, such as Vivendi, complain about a different agenda. Yves Picaus, the managing director of Vivendi water, a French water company in South Africa, says that peoples’ attitudes regarding water needs to change. He states that those who do not pay, do not care. Thus, the culture of “non-payment” is the problem.

Some places in South Africa charge up to 20% of the poor’s income for water (Carty 1). This intensifies the loss of social capital for the region. The poor are forced to choose between receiving water, getting an education, decent healthcare, or another essentiality.

Almost all the different communities in South Africa had horrible stories regarding their privatized water. Whether it is water meters, water guards, or not enough of water in their “Basic Free Water” ration, the South African poor suffer from water shortages.

In South Africa a new apartheid exists – a water apartheid.

Bolivia

Basic Statistics: Bolivia is considered “low” on the Human Development index. It has an 81.6% literacy rate, 52 (per 1,000 births) infant mortality rate, and 65.84 is the average life expectancy. Bolivia has a low average per capita gross domestic product income of U.S. $1,059 (see bottom country fact chart). This portion of the discussion will focus on Bolivia’s most infamous water privatization scandal in Cochabamba.

Water Privatization History: Early in the 1980s, the Bolivian economy was near completely wrecked by hyperinflation. Bolivia was one of the poorest countries in South America, and desperate for relief, Bolivia has been trying to recuperate ever since by selling most of the country’s assets (Finnegan). Since 1985, the Bolivian government has been trying to set a neo-liberal economic agenda to advance their economy into a global market, and to help recuperate their dismal economy. They have been trying to attract transnational investment attention since that date. They have been allowing for free trade and other conditions that would attract more international corporate interest (Fuente 99). Bolivia has sold almost all of the normally federally owned services, the airlines, mines, railroads, and electric companies to primarily foreign corporations. This massive sell-off of public enterprises led to a decrease in inflation, but also to a severe recession and exponential unemployment (Finnegan).

Also, unfortunately, both back in 1985 until now Bolivia has not had good, independent, professional negotiators who could fully understand the implications and contracts regarding international deals. Bolivia has succumbed to contracts from large transnationals such as the World Bank, the World Commerce Organization, and American’s Free Trade Association – all of whom do not rule in the citizens’ interests (Fuente 98). The World Bank pressured Bolivia into selling its remaining assets, including water (Finnegan). Bolivia is also known to have a very corrupt government, one of the worst in the global South, and there was widespread belief that the government officials and local elites were and still are being bribed into corrupt contracts (Fuente 99).

The state of Cochabamba, Bolivia in 1994 was that a third of the population had no connected water services at all. They needed investment in their water supply so that they could receive it. The corrupt, indebted, and inefficient Bolivian government could not provide the investments necessary at that time to assist in Cochabamba’s water plight. In 1998, the World Bank refused to refinance water system in Cochabamba, Bolivia unless the government sold their public water services to be privatized (Fuente 98). The World Bank then allowed for absolute monopoly for the private water concessionaires and declared that the cost of water be rated at the American dollar and that “none of the loan could be used to subsidize for poor water services (Barlow 31).”

Only one bid was really considered. Cochabamba’s water services was divvied up to where 50% of the shares were bought by International Water Limited, a subsidiary of a powerful engineering and construction company out of San Francisco, part of which was also given to the Edison company out of Italy; 25% of the company was bought by Abengoa, a company out of Spain; and the remainder was allowed to be owned by Bolivians (Feunte 98). By December of 1999 the private sector announced that the water prices would increase 100%. In Bolivia, for most people the cost of water would be more than for food (Barlow 31). Everyone, from the urban professionals to the peasant irrigation cooperatives were required to be hooked up to the monopoly water supply. On the assumption that those without water services would eventually receive it, those who did not even have access to water at that time were also billed.

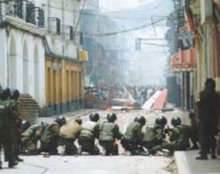

The attempt to privatize water in Cochabamba, Bolivia and the disastrous consequences is poignantly portrayed below.

....The attempt to privatize water in Cochabamba, Bolivia, is possibly

the

most infamous failure of privatization to date. Cochabamba

is the

third-largest city in South America's poorest country, Bolivia.

It has weak

infrastructure — only half of its 800,000 residents

have running water - but

is growing fast as rural privatization

pushes the unemployed to urban

areas…..

….Bechtel drastically increased water prices and the city

came to a standstill

as the people of Cochabamba protested in the central

plaza and blocked the

streets. The government attempted to stop the protests

through use of the

police and other security forces, and later by declaring

a state of siege. More

than 170 people were injured and one 17 year old boy,

Victor Hugo Daza,

was shot in the face and killed. When Bechtel finally

withdrew, the violence

stopped. The people of Cochabamba regained control of

their water system.

Bechtel is now suing the Bolivian government for $25

million, a portion of

the profit the corporation had hoped to make, but

didn't ("Privatization of

Water in Cochabamba, Bolivia").*(see note

below)

*Bechtel has since upped their lawsuit against Bolivia to $50 million, 25 million for damages and 25 million for lost profits. Bechtel has also, however, dropped the suit and left Bolivia in 2006, turning the water back to public ownership (“Bechtel Drops $50 Million”).

Before Bechtel withdrew, there was widespread violent opposition and protests against the water contract and other forms of extraordinary support to break the contract with Bechtel. The government sent out their military to subdue some of the opposition, resulting in many injuries, deaths, and even more distrust.

The demands of Coordinadora de Defensa del Agua y de la Vida (Coalition in Defense of Water and Life) to amend the water laws were accepted. A newly created organization established in 2000, Coordinadora de Defensa del Agua y de la Vida is made up of professionals, manufacturing unions, enterprises, cocoa leaf producers, and peasants were accepted. This coalition was the first acclaimed space where men, women, children, and the elderly were able to demonstrate against neo-liberal policies that consumed their lives (Olivera 53).

Other grassroots organizations have pushed for and succeeded in telling the government to change the laws regarding water. They have also pushed for the re-classification of water to be considered not as a commodity but as a public good (Fuente 99). The regantes peasant associations who control the irrigation systems in Cochabamba’s fields were the key movers and shakers in the water conflict. Their goal was to build a national movement or organization to gain social control over the public entity SEMAPA, the enterprise in charge of the water supply.

The Bolivian water privatization situation is similar to South Africa’s except the water privatization was more localized to Cochabamba and there has been more of an organized push from the people. The incredible organization of people is what pressured Bechtel to reconsider and leave.

Little to no American newspapers have reported what has happened in Cochabamba, even with a major U.S. corporation, Bechtel, being the center of the scandal. Thanks to the internet, however, the water plight in Bolivia has reached international audience.

IV. Non-governmental Organizations Working on the Issues

Governments have always dominated water policy decision making. In the last few decades, however, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have played a growing role (Lane 78). The types of non-governmental organizations include: local and international, representative and self-created, those active in fieldwork, advocacy, or research. Some of the NGOs that are active in the water privatization fight in each country are:

United Kingdom: Water Aid (Lane 78)

South Africa: Mvula Trust, Coalition Against Water Privatization by Phiri Concerned Residents, Soweto Electricity Crisis Committee, Anti-Privatization Forum and Khanya College, Jubilee South Africa and other progressive non-governmental organizations (Lane 78 & Ka-Manzi).

Bolivia: FEJUVE, Coordinadora de Defensa del Agua y de la Vida (Olivera 53)

Water Aid: The people and organizations of the British water industry founded Water Aid in 1981 to assist poor people in developing countries improve their lives through improved drinking water, sanitation, and hygiene. They achieve this by working through partner organizations to support community managed projects so that eventually their partners (governments and local NGOs) can take over the work without dependency on Water Aid. They also work on influencing other organizations to lend support to the local problems at hand. The UK’s membership Water Aid membership pool include all the members of the Water Research Centre, the Chartered Institution of Water and Environmental Management, and the Institution of Water Officers, and all the water authorities in England, Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland (Lane 78).

In South Africa organizations such as the Coalition Against Water Privatization in South Africa (CAWP) consists of community based and non-governmental organizations that have been organizing and advocating for South Africans’ right to adequate and affordable water access (Ka-Manzi).In Bolivia, organizations like the Federation of Neighborhood Organizations in the City of El Alto, Bolivia (FEJUVE) is a non-partisan, civic organization organized to advocate for social justice and equality in the town of El Alto, a small suburb of La Paz. The El Alto community has 68% of their community living below the poverty line while 45% have no access to potable water. Their secretary general was appointed water minister by newly elected President Evo Morales, who declared that Bolivia will no longer allow privatization of water services (Lane 78).

In Bolivia, the grassroots organizing efforts of groups such as Coordinadora de Defensa del Agua y de la Vida effectively helped change water policy and help throw the water company out of their country. As in South Africa, the organized collaboration of multiple citizens’ groups helped to revise water policy and a Free Basic Water ration policy was enacted because of their efforts. These citizen groups are therefore essential in pressuring governments to modify existing policy or create more democratic water guidelines.

Unfortunately it is only after their water prices rise that more people organize to protest the influence of water companies. This indicates that the people probably felt that their water was either better before privatization, no change had occurred as a result, or that paying more for water was beyond affordability. Non-governmental organizations and community-based, grassroots efforts have been and will continue to be the primary movers and shakers in continuing to change water policy for the benefit of all, not just the few.

V. The Challenge to Make Privatization Work

Given the case studies above, it is obvious that each country, and/or community within each country have differing situations regarding water management and privatization. No ubiquitous prescription should be considered regarding what can work if privatization of water becomes and option. The below recommendations, however, can provide a general outline regarding privatization contracts should be viewed to ensure more equitable water access (Gleick et al. 10-12).

Responsibility of All

1) Make sure basic ecosystem and human needs for water are met. There should be a guaranteed basic water quantity required under any privatization agreement for all living things, thus life can sustainably continue.

This recommendation was tried in South Africa in the Free Basic Water Policy Act where there was a promise to provide a minimum amount of water for free on a daily basis (McDonald and Ruiters 99). However the amount provided should be reasonably adequate and changes should be made if someone has a greater need for more water, such as those who work in unclean environments, the sick, etc. “Free water” should be available to everyone no matter what the income level, the first amount of water should not be charged. After exceeding the free allotment of water the cost can then rise according to the extra amount of use.

2) Basic water requirements for users should all be provided at subsidized rates when necessary, especially for poverty reasons.

England and South Africa have taken steps to do this. England and Wales offer alternative charging options and consumers have the right to free optional metering. South Africa offers rebates in pricing after people exceed the free water ration amount.

3) Transparency of water service policy, so the public is informed of the rate hikes thus encouraging more efficient and effective water utilization.

In all the studies mentioned the public was outraged due to the increase in their water prices. There seems to have never been a publicized effort to inform the public of why privatization of their water was happening and what the company promises to offer. By making the water policy transparent it increases pressure for companies to be held more accountable and the public are more likely to understand how they can change service policy if it is violated.

4) Water privatization contracts should be public, transparent, include appropriate language for all readers, and include all affected stakeholders.

As much as possible, the people affected should be educated on what the privatization of water means to them, their budgets, and the supposed improvements that will ensue. The private negotiations that happened in England, Wales, South Africa, and Bolivia, all contributed to the upset of the people who felt as though their voices were not heard and they were not informed of the supposed benefits to water privatization. The education of the public on the water policy could also better equip them on how to change policy.

Responsibility of Water Company

5) Pre-arranged profit caps for water companies.

England and Wales once has a history of mixed ownership and at one time some private water supply companies actually had a maximum profit cap of 5%. This is a basic recommendation to make sure that all water companies. The profit motive can then be reduced and thus assure that the water prices for the people are not to rise above a certain amount.

6) Link a rate increase with formerly agreed upon improvements in service.

This recommendation stems from the indication that the public, governments, and water companies should have standards on what is considered an improvement in service, how much should the price be increased, and if it is actually needed.

7) Companies must prove that there is a necessary investment change in water management infrastructure to attest water price hikes.

Included in a pre-arranged contract, a required evaluation should be conducted before water price hikes to see if a change is absolutely necessary. Water pricing hikes should never exceed the demographics’ affordability range. This recommendation would have been very appropriate for all the case studies above, especially in England and Whales when the quality of water reportedly declined after privatization (Barlow 26).

8) A provider should be allowed some freedom in water management decisions, but not be able to renegotiate the agreement when profits decline.

Although the company should be held responsible for the knowledge regarding what water management decisions are appropriate for a particular region, additions or modifications to the pre-arranged contract should never happen unless there is agreement with the public and local government that a modification is needed.

Responsibility of Governments

9) Governments should define and enforce water-quality laws.

If you cannot measure something how can you accurately and efficiently manage it? In the case of water, all governments should publicize a regular assessment of: where the local water comes from; what is in the water; what are the possible contaminants; how they are trying to remove the contaminant particulates; enforceable consequences on those who contaminate the water; how much money is needed to manage water services; and whatever else is deemed necessary for the water quality of the region. With this initial strategy on the state of water and services related to it, the option to privatize water can become clearer on what reasons prompt for privatization. This recommendation could possibly have reduced some of the rioting and confusion that ensued in South Africa and Bolivia when some of the reasons why people could have been upset were maybe that they did not understand why they needed investment or the increase water prices.

10) Governments should continually monitor water quality to provide oversight of the private companies.

This recommendation is essential to ensure that the companies do not deviate from their contracts.

11) Independent technical assistance and contract review should be standard.

This recommendation stems back to the citation about when in 1985 Bolivia did not have good, independent, professional negotiators who could fully understand the implications and contracts regarding international deals. Bolivia succumbed to contracts from large transnationals such as the World Bank, the World Commerce Organization, and American’s Free Trade Association. Although these institutions should be considered “independent technical assistance” in many cases many poorer countries yield to contracts from transnational organizations who, in many reported cases, do not rule in the citizens’ interests. Somehow, either a new world organization or a re-evaluation and modification of the current ones needs to happen to provide poorer countries objective advice on what really needs to be done to improve water services.

12) Allow for local water companies to be given priority in bids for the water

appropriation; only if they contract to provide service standards equal to the competitions’ claims.

The proliferation of globalization has caused for an increase in absentee “ownership” of water and other public commodities. This can lead to countries being vulnerable to international fluctuations in price, war, sanctions, and various political upheavals that may or may not have started in their own country but nonetheless they are affected because their water is not owned by them. The foreign water company can thus hold some authority in another country’s political and economic situations. Local companies are more likely to be amenable to changes in water service policy, especially if those who work for the company live in the affected area.

13) Allow for multiple bidder consideration, thus encouraging competition and no monopoly of a community water supply.

Although not always possible or efficient, multiple company ownership could over a particular area’s water supply has the capacity to create competition, helping to reduce prices and to provide better quality water.

14) Consider privatizing water as a last resort and find other ways to fund expenses, reduce public borrowing, or reduce debt.

Possibly one of the most difficult of recommendations, in many cases, such as England and Wale’s want to reduce public borrowing and Bolivia’s need to reduce federal debt, the selling off of public commodities such as water has notoriously proven to provide unexpected or negative results. Governments need to carefully evaluate their budgets, country’s political, social, and economic conditions so they can best provide strategies and alternative options on how to fund projects, reduce public borrowing, not increase taxes, and reduce federal debt without selling off their water services. Every country and community is different, thus no ubiquitous prescription should be given on how this can be accomplished in every situation.

There are many more recommendations on how privatization can work. Unfortunately, many recommendations need the government to be participatory and democratic. In many cases such government oversight sometimes defeats the purpose of why a locality would privatize anyway, to decrease governmental influence and for someone else to make the tough water management decisions. The best situations should involve the citizens, the water companies, and the local governments to work in partnership with one another so that all can receive equitable, clean, and reasonably priced water services.

Conclusion

Water privatization is a fairly new globalization trend and tool. A majority of the water privatization transactions have happened within the last two decades. With the current world-wide water crisis, further investment in the watersheds and infrastructure will be needed, and more money will need to be found for better filtering system and infrastructure. Therefore the water privatization movement does not look like it will decline any time soon.

When the price for water services increase, water privatization does provide a disincentive to use more water, and the conservation incentive is addressed. However, when the price rises so high and water services are cut off, the conservation measure has gone too far. Therefore it is very critical that the “kinks” be worked out of the current models of water privatization. It seems as though we are in an experimental period of water privatization, where trial and error is the norm. We must find ways to not treat water privatization as an “experiment” but rather as an effective opportunity to help assuage the world water crisis.

The understanding of how water privatization works is truly complex, and each time water privatization is to be considered, governments must take into account the differing demographics, social, and economic impacts that water privatization can have on the communities to be affected. There seems to never be a publicized, pre-met consensus from the people regarding who they want to govern their water needs. Although the governments may not always have the capital to invest in needed improvements in water management, if the water companies invest in the water systems but raise the price for water so high that people cannot afford it, which option is better? The studies indicate that a raise in water pricing does not always parallel improvement in water services, nor that more people are actually hooked up to water lines. The studies point out that where-ever water privatization occurs it will always need the partnership of the people affected, local and national governments, and the water companies.

When countries ask for or are subjected to outside business to come and run their water management systems, they are often leaving themselves vulnerable to unfair contracts, loan stipulations, absentee ownership and much more. South Africa and Bolivia face governmental organization and/or fiscal/debt difficulties, thus requiring active federal participation in water management contracts is not easy. The lower United Kingdom, being a “first world” country, had an easier time working on their water privatization kinks and were able to find some reasonable solutions to some of their problems. Due to having more capital, and more democratically based and less corrupt government, England and Wales will probably never experience the same difficulties in water privatization as South Africa and Bolivia.

The motives to why water privatization needs to occur must be more carefully evaluated. Whether it is to encourage conservation measures and improve water quality such as in the England and Wales; enable more people to have access to clean water such as in South Africa and Bolivia; or to assist in reducing government debt such as in all cases; a before and after evaluation of a country’s water management systems must happen before resorting to privatization. It looks to be that in many of the cases the governments are making the decisions for the people for the sake of money reasons. Are there other ways that a government can reduce public borrowing and still make money other than selling off public assets?

The dramatic influence of organized people through protests, rioting, and non-governmental organizations to pressure governments to change water policy is critical. The voices of the people are heard more effectively when they are organized and water policy changes as a result. However the studies indicate that the people organize against privatization after, not before implementation. This indicates that not only were the people probably unaware of the upcoming changes, but that they probably felt that there was no improvement in water quality or allocation, or that their water worsened as a result. Most likely, they probably considered the increased prices were beyond affordability.

The choice for most communities is government versus business. The option to leave their water woes to the governments is difficult because they are often characterized as inefficient, corrupt, indebted, or ineffective. Hopefully an effective and improved “French model” of privatization (public/private partnership) can be created. This would allow for the people to have a voice, the governments the ability to have oversight, and the companies to provide the proper services. The appropriate implementation of the recommendations mentioned above could yield effective water privatization models. More studies, however, need to become available on the good and effective water privatization models in other countries; the overwhelming majority of studies only account for the attempted, unsuccessful strategies and the negative effects.

Works Cited

Bakker, Karen. “Archipelagos and networks: urbanization and water privatization in the South.” The Geographical Journal. Vol. 169:4. (1999). pp 328-341.

Bakker, Karen. "Deconstructing Discourses of Drought (in Exchange: Privatizing Water, Producing Drought)." Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers New Series. Vol 24: 3. (1999). pp. 367-372.

Bakker, Karen. "Paying for Water: Water Pricing and Equity in England and Wales." Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers New Series, Vol. 26:2 (2001). pp. 143-164

Barlow, Maude. “The Global Water Crisis and the Commodification of the World’s Water Supply.” 2001. 20 March 2007. http://www.blueplanetproject.net/documents/BlueGold_revised_01.pdf

“Bechtel Drops $50 Million Claim to Settle Bolivian Water Dispute.” Environment News Service. 19 January 2006. 6 May 2007.

http://www.ens-newswire.com/ens/jan2006/2006-01-19-04.asp

http://www.ens-newswire.com/ens/jan2006/2006-01-19-04.asp

Carty, Bob. “The Water Barons: A Look at the World's Top Water Companies.” Backgrounder. 3 February 2003. 29 March 2007. http://www.cbc.ca/news/features/water/business.html

Fuente, Manuel de la. “The Water War in Chochabamba, Bolivia: Privatization Triggers an Uprising.” Mountain Research and Development. Vol 23:1. (February 2003). pp. 98-100.

Gleick, Peter H.; Wolff, Gary; Chalecki, Elizabeth L.; Reyes, Rachel. The New Economy of Water: The Risks and Benefits of Globalization and Privatization of Fresh Water. Hayward, California. Alonzo Environmental Printing Co.: 2002

Joy, Clare & Hardstaff, Peter. "Dirty Aid, Dirty Water: The UK Government's push to privatize water and sanitation in poor countries." February 2005. 25 April 2007. http://www.wdm.org.uk/resources/reports/water/dadwreport01022005.pdf

Ka-Manzi, Faith. "African Water is Not for Sale." 19 February 2007. http://www.ukzn.ac.za/ccs/default.asp?2,40,5,1244

Lane, Jon. “Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs): New Players in Water Policy.” ITT Industries Guidebook to Global Water Issues. 29 April 2007. 78-79

Lobina, Emanuele & Hall, David. “UK Water Privatisation – a Briefing.” 2001 February. 29 March 2007. http://libcom.org/library/uk-water-privatisation

McDonald, David A. & Ruiters Greg. The Age of Commodity: Water Privatization in Southern Africa. London; Sterling, VA : Earthscan, 2005.

Olivera, Oscar. Cochabamba!: Water Rebellion in Bolivia. Cambridge, Massachusetts. South End Press: 2004.

"Privatization of Water in Cochabamba, Bolivia." International Budget Project. Bimonthly No. 15. Newsletter. May 2003.

Saal, David S. & Parker. David. “The Impact of Privatization and Regulation on the Water and Sewerage Industry in England and Wales: A Translog Cost Function Model.” Managerial and Decision Economics. Vol. 21:6. (September 2000). pp. 253-268.

Segerfeldt, Fredrik. “Private Water Saves Lives.” CATO Institute. 29 August 2005. 4 May 2007. http://www.cato.org/pub_display.php?pub_id=4462

Taylor, Liba. “Water Privatisation in South Africa.” Actionaid. 2006. 28 April 2008. http://www.actionaid.org/main.aspx?PageID=326

Troesken. Werner. “Typhoid Rates and the Public Acquisition of Private Waterworks, 1880-1920.” The Journal of Economic History. Vol. 59:4. (December 1999). pp. 927-948.

“The Water Industry: An Unrefreshing Look” Corporate Accountability International. 4 May 2007. http://www.stopcorporateabuse.org/cms/page1131.cfm